Magic Merlins – 751 Squadron

Esquadra 751 ‘Pumas’ was named after the helicopter it received when the squadron was commissioned in April 1978, the SA330 Puma. By the turn of the century the SA330 needed replacement and the AgustaWestland EH101 Merlin was selected after a thorough evaluation, which also included the Sikorsky S-92 and Eurocopter Cougar.

Twelve Merlins were delivered between December 2004 and July 2006, comprising six models EH101-514 for Search And Rescue (SAR), two EH101-515 for fishery patrol (SIFICAP), and four EH101-516 for Combat Search And Rescue (CSAR). While the latter two models are specially equipped for a secondary role, all helicopters are being used for the squadron’s primary mission of Search And Rescue.

Initial maintenance issues and lack of experienced crews sparked the Portuguese Air Force to bring the SA330 back in service shortly after retiring it in 2006. A lack of spares led to half the Merlin fleet (mainly SAR versions) being grounded in order to provide spare parts for the other six helicopters. A contract signed in 2008 with AgustaWestland, saw the manufacturer take responsibility for secondary-level maintenance of the helicopters as well as the provision of spare parts and technical support. This has led the entire fleet of Merlins to become operational again.

Under the command of LtCol João Carita, who is one of only three pilots in the world with over 2000 hours on the EH101, Esquadra 751 consists of around 100 personnel, including some 25 pilots, 12 systems operators and nearly 20 rescue swimmers. Defence budget cuts have affected the squadron’s flight hours, but the importance of their mission is such that other Portuguese Air Force squadrons have been hit harder. The number of flight hours logged by the squadron decreased from 2208 in 2011 to 1744 in 2012.

In terms of operational SAR missions, in 2011 the squadron logged 608 hours while saving 173 lives. These numbers decreased to 430 hours and 157 lives the next year. Each pilot flies a rough average of between 150 and 180 hours per year. Although this may seem a very fair amount, this includes frequent rescue missions, leaving only around a hundred hours for training.

One pilot told the author he scrambled into action for the past three consecutive 24-hour shifts he was on alert. If there is a sudden increase in rescue missions, or an increase in flying distance to emergency locations, pilots will get less training.

At six million square kilometers, Portugal has the largest area to provide SAR coverage for in Europe. In fact, Portugal is responsible for the second largest area worldwide, only behind Canada. Besides operating from the squadron’s homebase Montijo (near Lisbon), two Merlin crews are permanently detached to Lajes airbase in the Azores (some 850 miles west of Portuguese mainland) and an additional crew is detached to Porto Santo airport (440 miles west of Casablanca, Morocco).

In order to have the helicopters deployed as long as possible they only fly when called into action. All three locations are provided with round-the-clock SAR coverage. The response time is 30 minutes during the day or 45 minutes at night. Since crews at Porto Santo are accommodated off-base, they require an additional 15 minutes.

Deployed crews generally stay for two weeks. At Lajes they alternatively work 12 or 24-hour shifts, while at Porto Santo they are on standby 24/7 for the whole duration of their deployment. Lajes tends to get the most alert calls, due to tropical storms and its strategic position astride major shipping lanes between Europe and the Americas.

Pilots with previous experience on the Puma told the author they prefer it over the Merlin when it comes to hovering over a ship, but they love the EH101 in all other aspects. In the Puma it was very easy to look down, whereas pilots are seated further away from the side windows in the EH101, making communication with the systems operator hanging out of the cargo door even more important during winch operations.

The Merlin’s range of up to 400 miles, double that of the Puma, has been a major improvement. Several missions have already been carried out as far away as 350 miles offshore. Lieutenant Ricardo Nunes, pilot-in-command on the EH101: “Long-range missions bring planning to a whole new level. Every small factor can influence the mission. For example, if the sea state is worse than expected it might take a couple more minutes to rescue someone from a ship. You can imagine how this adds up if we have to rescue ten or more people. So, in long-range SAR missions a good plan is essential.”

”We often fly OEI (One Engine Inoperative) profiles in long-range missions because it gives us a 12% saving in fuel consumption. When you have someone’s life at risk in the middle of the Atlantic, at night, in stormy weather, that can make the difference.”

Another pilot explained how the wind affects their range more than it does an aircraft, because of a helicopter’s relatively low speed and its non-streamlined design. On one occasion, they planned to do a long-range mission with a strong headwind on the way to the scene. On the way back the tailwind would easily take them to solid ground. However, the wind turned and they faced it again on the return flight! They made it back with just enough fuel, but it was a very close call.

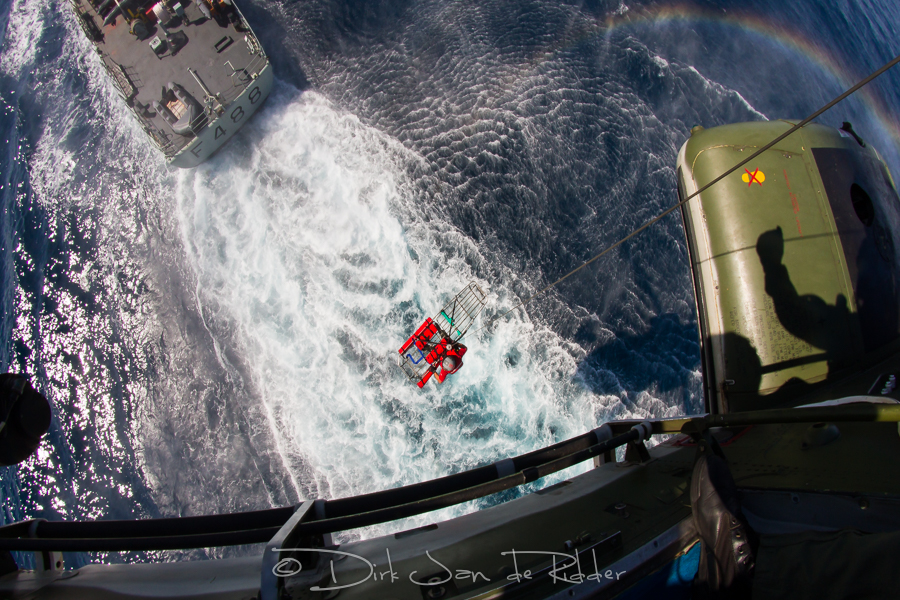

A typical SAR training mission from Montijo lasts two and a half hours and will see a crew of four fly out to the ocean, looking for a random vessel willing to cooperate with their training. As a rule, the Merlin will position at 60 feet above the vessel moving sideways at the exact same speed and in the same direction of the ship. This will allow the systems operator and rescue swimmer to carry out their training. Depending on training requirements they will winch down a dead weight or the rescue swimmer, with or without a stretcher or a real-weight training dummy. The same types of winch training are frequently carried out in the water and near cliffs along the coast during the same flight, as well as at night.

Sometimes multiple systems operators or rescue swimmers get their training on a single flight, which can become a little uninteresting for the pilots when it comes to hovering over open sea for dozens of minutes. Ship training never gets boring though. The level of concentration needed for it wouldn’t allow for it anyway. Other frequent types of training include tactical flying, IFR and VFR navigation flights, exercises with force protection and special force units, general handling and emergency training.

It is Monday morning 30 March 2010, half past six, and 751 Squadron’s phone rings. A vessel named ‘Kea’ from Barbados, carrying 24 people is sinking 170 miles off the coast of Cape Finisterre, Spain (to the north of Portugal). Ground personnel quickly install an external fuel tank before ‘Rescue23’ takes off. Lieutenant Nunes, the co-pilot on this mission, picks up the story as they approach the ship after a 400-mile transit: “As we reached the area, the scene was like a Hollywood movie. The sea was very rough with waves up to seven meters. We found the Kea turned upside down, with the bow slightly raised and we could see almost the entire hull. The sailors were already in the water so there was no time to lose.”

“We decided to go into the hover immediately and rescue three victims floating in line, clinging to a cable. Their anti-exposure suits were filled with water causing them to be in a state close to hypothermia. Some others had in the meantime been picked up by nearby ships. After rescuing two more sailors, we initially decided to remain on station looking for two sailors still missing, but after consulting rescue coordination and due to the status of the sailors already on board we decided to head back to Santiago de Compostela, where we had refueled earlier in the morning.”

The sailors were taken to hospital and the helicopter crew takes a well-deserved break, before returning home later that afternoon. Comprising 8 hours and 30 minutes of actual flying time, and the distress call coming from just over 400 nautical miles from their homebase, this rescue still is the Portuguese Air Force’s longest search and rescue mission, both in terms of flight time and distance covered. For their effort, the Spanish maritime rescue and safety agency SASEMAR awarded the crew with the ‘Silver Anchor 2010’, but for them it was just another day in which they lived up to their motto ‘So others may live’.

A full report appeared in several magazines, including in AirForces Monthly:

Comments are closed.